A Sculptor of Sound: Celebrating Pierre Boulez on his 100th Birthday

Pierre Boulez (1925–2016) inspired generations of musicians and listeners as a composer, conductor, and pedagogue of exceptional caliber and generosity.

Pierre Boulez (1925–2016) was a luminary of 20th-century music, inspiring generations of musicians and listeners as a composer, conductor, and pedagogue of exceptional caliber and generosity. He spent a great deal of time with The Cleveland Orchestra in the 1960s and ’70s as a guest conductor and then as musical advisor, ushering the group through the uncertainty following George Szell’s death in 1970. The relationship remained strong, and in the 1990s and early 2000s he returned nearly annually to lead concerts and recording projects. Boulez recorded more than 50 works with the Orchestra, five of which earned Grammy Awards. 2025 marks the 100th anniversary of Pierre Boulez’s birth, and institutions around the globe are paying homage to his tremendous impact. The Cleveland Orchestra joins this chorus, celebrating our five-decade relationship with Boulez and honoring his larger musical legacy.

November 13–23 visit our exhibit, Boulez in Cleveland, in the Grand Foyer.

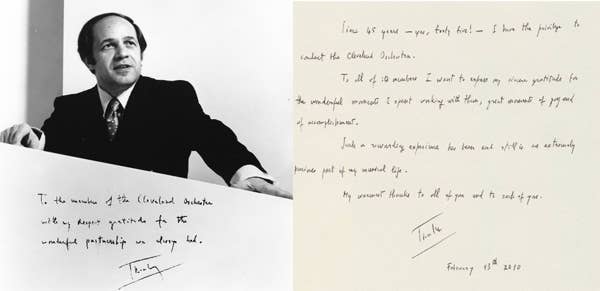

- The exhibit includes manuscript reproductions of Boulez’s compositions he conducted with TCO, letters related to his time in Cleveland, and photographs spanning five decades of collaboration.

Early Life

Pierre Boulez was born on March 26, 1925, in Montbrison, France. As a child, he nurtured passions for music and mathematics, deciding on music (against his father’s better judgment) only upon entering the Paris Conservatoire in 1942. After three years, Boulez collected the premier prix in harmony and began looking beyond the Conservatoire for compositional inspiration. In choosing music, Boulez had not left mathematics behind. His penchant for methodical and algorithmic composition techniques drew him to Arnold Schoenberg’s twelve-tone method, which he studied with René Leibowitz, applying Schoenberg’s principles to musical considerations far beyond pitch in a nascent technique known as total serialism. Boulez’s other composition teachers included Olivier Messiaen, with whom he studied at the Conservatoire, and Andrée Vaurabourg.

Boulez identified with a group of young firebrand composers who believed that music ought to capture the anxiety of the moment and were not afraid to criticize the old guard of modernists when they fell short of that mark. Soon after leaving the Conservatoire, he found opportunities to spread his influence as a conductor as well as a composer. In 1946, Vaurabourg’s husband, composer Arthur Honegger, recommended Boulez as music director for Jean-Louis Barrault and Madeleine Renaud’s theater company. This proved to be an important connection for Boulez; with the support of the Compagnie Renaud-Barrault, he founded the Concerts Marigny in 1953 (rebranded the Domaine Musical the following year). For the next 15 years Boulez served as music director of this popular and ground-breaking Parisian series, featuring cutting-edge compositions from across the world and premiering many important works.

It was not long before Boulez was conducting outside of France. The Compagnie Renaud-Barrault went on tour annually, which brought Boulez to the United States for the first time in 1952. On the 1956 tour to South America, Boulez led the Venezuelan Symphony Orchestra in a program of Debussy, Stravinsky, and Prokofiev — his first time at the helm of a large symphony orchestra. In 1957, he went to Cologne to premiere one of his own works and was back within the year to conduct the Southwest German Radio Symphony Orchestra. In 1959, he moved to Baden-Baden to conduct that orchestra full-time, very publicly denouncing the state of modern music in Paris. Boulez returned to the US in 1957 and 1963 as a lecturer and guest conductor, but his March 1965 appearance with The Cleveland Orchestra would mark his first appearance with a major American orchestra.

Boulez in Cleveland

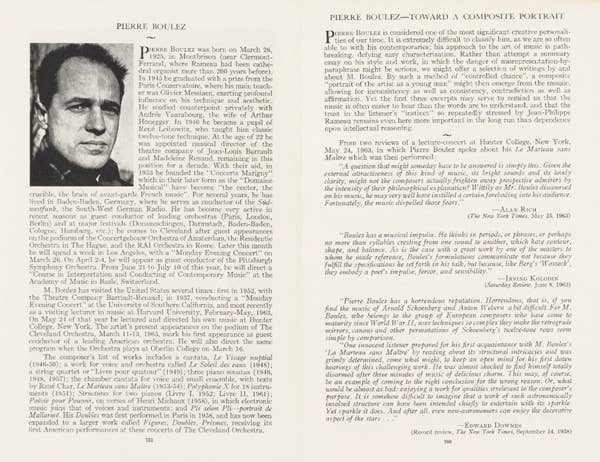

Boulez’s major debut in Cleveland was no chance occurrence. Over dinner in Europe in 1963, Music Director George Szell invited the rising European star to guest conduct the Orchestra, and Boulez graciously accepted. The program Boulez led at Severance Hall that first visit was quite similar to the concert he conducted in Venezuela a decade prior — a collection of modernist works that presented a slightly more palatable version of the extremist aesthetics he expounded in his youth. The key difference was that this concert featured one of Boulez’s own compositions: the US premiere of Figures — Doubles — Prismes. Boulez’s appearance was not that of an average guest conductor. The program book featured not only a biography of the composer/conductor and detailed program notes for each piece (including words from Boulez about his own composition) but also no fewer than five pages of quotations by and about Boulez to offer a “composite portrait”:

Pierre Boulez is considered one of the most significant creative personalities of our time. It is extremely difficult to classify him, as we are so often able to with his contemporaries; his approach to the art of music is pathbreaking, defying easy characterization. Rather than attempt a summary essay on his style and work, in which the danger of misrepresentation-by-paraphrase might be serious, we might offer a selection of writings by and about M. Boulez. By such a method of “controlled chance,” a composite “portrait of the artist as a young man” might then emerge from the mosaic, allowing for inconsistency as well as consistency, contradiction as well as affirmation.

Listen to a live recording of Boulez conducting Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring in Severance Hall on November 9, 1967. Two years later, Boulez’s recording of this piece would earn The Cleveland Orchestra their first Grammy Award.

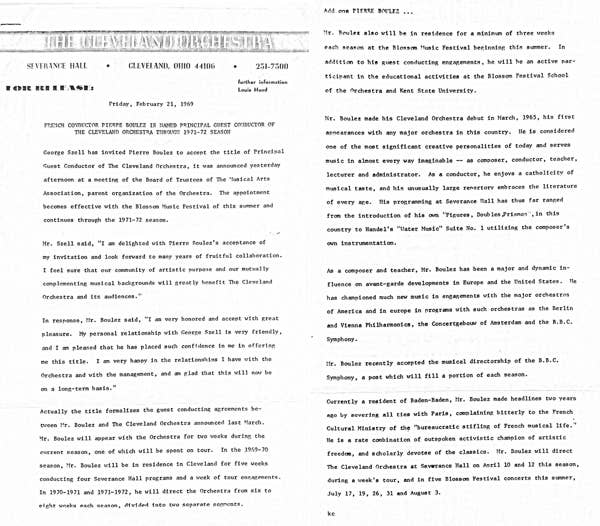

Szell was happy with Boulez’s performance and invited him back in 1967. That same year Boulez entered into a five-year guest conducting agreement with The Cleveland Orchestra. This arrangement was so successful that, in 1969, Boulez became the Orchestra’s first-ever principal guest conductor.

Boulez was conducting a concert at Blossom on July 30, 1970, when the news of Szell’s untimely passing reached the Orchestra. Assistant Conductor Louis Lane delivered the news to Boulez at intermission, and he promised to share the news with the musicians only after the concert. Just months before, Szell had encouraged Boulez to accept an offer for music directorship of the New York Philharmonic. Going into the 1971–72 season, Boulez was not only embarking on that new journey but also stepping into the same role with the BBC Symphony Orchestra in London. Despite these two exciting and demanding endeavors, Boulez agreed to serve as musical advisor to The Cleveland Orchestra for the following two seasons, ushering the organization through the upheaval in the wake of Szell’s loss.

Boulez was conducting at Blossom the night George Szell died. Listen to the haunting second movement of Brahm’s second piano concerto, performed by Misha Dichter with Boulez and the Orchestra on that fateful night.

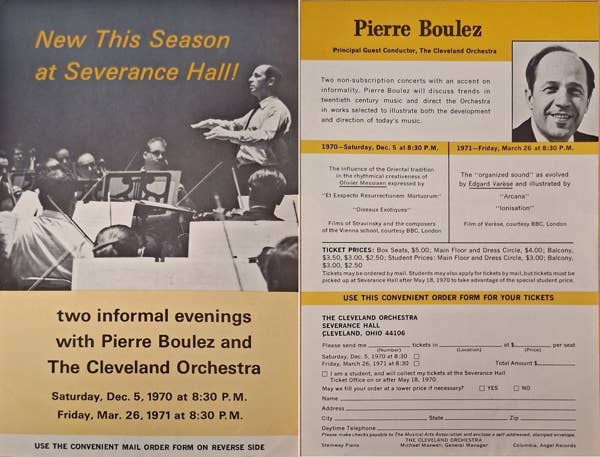

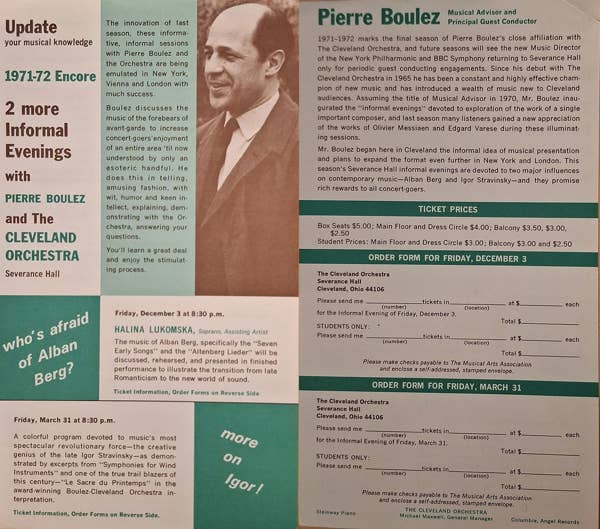

It was during his stint as musical advisor that Boulez hosted a series of “Informal Evenings” — two annual concerts of new music interspersed with lectures from Boulez.

Advertisements for Boulez’s first Informal Evenings in the 1970–71 season highlighted the casual nature of this miniseries.

Frank Hruby wrote enthusiastically about the first concert in December 1970:

With the use of an overhead projector and a lavalier microphone Boulez played teacher to some 1500 patrons who got what they paid for — a lesson in mid-20th century music. He is an excellent teacher, as the music world knows and as Saturday’s audience experienced. The clarity of thought which makes him so that his pronounced French accent lent Gallic charm [rather] than confusion.

Robert Finn of The Plain Dealer commented on the depth of information and the size of the audience: Boulez “shed as much light on the music of Olivier Messiaen in two hours as most people get from two decades of listening and study. … This program was frankly an experiment. While it did not sell many tickets, there is no question that it was an artistic triumph.”

While no photographs or recordings survive from the Informal Evenings themselves, Boulez selected repertoire that was on the Orchestra’s regular schedule. Here is a recording of Olivier Messaien’s Oiseaux Exotiques from a subscription concert November 19, 1970. Boulez carefully took this piece apart for audiences a few weeks later at the first ever Informal Evening (December 5, 1970).

After the second concert in March of 1971, William Salisbury noted some improvements from the last time: “the proceedings became more relaxed, the teacher-conductor more spontaneous, the musical examples more simple and the audience more responsive.” His article ends with the strong conviction for “a need to have a continuing series concentrating on contemporary composers whose music is at last being introduced to Severance Hall audiences.”

The concerts were never well-attended, though, and reviewers were never unequivocal in their praise, remaining critical of both their format and execution. Robert Finn’s review of the December 3, 1971 concert (the first of the second season) was titled “Boulez’ Artful Blend Falls Short in Parts,” but ended on a congratulatory note: “This program, despite disappointments at beginning and end, is the kind of thing Pierre Boulez does best. Let him find reward in this remark overheard after ‘Seven Early Songs’ : ‘My husband says he’s beginning to like this kind of music!’ The Berg magic is working on Severance audiences — and high time.” Hruby lamented the end of the short-lived series after the last of the four concerts, writing, “Isn’t that the way it always is? Just when a new idea begins to take hold and attract a following, it’s over and done with. … Perhaps Mr. Boulez could be prevailed upon to come back for an evening or two each season for more lessons?”

On December 3, 1971, Boulez walked audiences through the works of Alban Berg, including his Seiben frühe Lieder (Seven Early Songs). Here is a recording of the sixth song, “Leibesode” from a subscription concert the evening prior. Soprano Halina Lukomska joins Boulez and the orchestra in this performance.

Despite their brief life span and lukewarm reception, these concerts provided an important blueprint for several series Boulez later hosted in London and New York. The Perspective Encounters took place in both cities and were intended to “get rid of the idea that in listening to new music we’re discovering masterpieces of the twenty-first century,” according to Boulez (La Monde, February 3, 1972). Instead of putting new music on a pedestal, in other words, he wanted to make the music as accessible and comfortable for listeners as possible. The Rug Concerts (1974–77) also featured new music in a casual and welcoming context, in this case because the seats were removed from Philharmonic Hall in New York.

In his years with an official appointment in Cleveland (1967–72), Pierre Boulez led the Orchestra in over 100 works spanning three centuries, including the Cleveland premieres of more than 30 pieces. He led the Orchestra at Severance, Blossom Music Center, and on regional runouts, in addition to joining the Orchestra on international tours to Montreal (1970, 1972) and Japan (1970). Unlike his somewhat difficult tenure in New York, Boulez experienced a warm welcome in Cleveland and built a close relationship with musicians and audiences alike. These meaningful connections would ensure that, despite his ever-multiplying international commitments and successes, Boulez would continue to return to Cleveland.

The program Boulez led on the 1970 Japan tour included American composer Charles Ives’s Three Places in New England. Enjoy this recording of the second movement of the suite, “Putnam’s Camp, Redding Connecticut,” from March 12, 1970. Boulez led the Orchestra in this performance in Cleveland, in preparation for their upcoming travels.

Career After Cleveland

Boulez remained the music director of the New York Philharmonic from 1971–77 and the chief conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra from 1971–75, continuing as chief guest conductor the following two years. In 1977, the Institute de Recherche et de Coordination Acoutstique/Musique (IRCAM) opened after four years of construction, and Boulez turned his full attention to his position as director.

Former Clevland Orchestra Women’s Committee Board member Carol Frankel cultivated a close relationship with Boulez, hosting him in her home for many years. In a reminiscence housed in the Archives, she describes a call Boulez received about this exciting project:

One morning at 6 AM, while we were all asleep in Pepper Pike, the phone rang in the Frankel house. There were no mobile phones in those days, and Maestro Boulez declined to have a telephone extension in his suite. I picked up the receiver next to my bed and a female voice with a decidedly French accent inquired for Maestro Boulez. When I mentioned that it was 6 AM in Cleveland, she said, “Madame, Monsieur Pompidou, the President of France, would like to speak with Maestro Boulez at this time.” Oops. I asked her to hold, jumped into my robe, and raced up the small steps to Pierre’s suite, knocked firmly on the door, and loudly said, “Pierre, I think the President of France is on the telephone and wishes to speak with you.” “Aha,” said Boulez behind his door. He put on his robe and opened the door. I ushered him into my office in the next room, lifted the receiver, went back to my bed, and carefully put my phone extension receiver back in its cradle. I was certain I must have been mistaken about who was calling and went back to sleep. That night at dinner, Boulez told us in detail that Pompidou, a cultured man, wished to make amends (that’s another story) and bring his most famous expatriate and “enfant terrible” back to France, Boulez told us that he knew this peace offering was coming and he had entirely thought through what he would demand to return to France on his terms: a three-story underground musical institute, a home for musicians and composers in residence who, like Boulez, wished to advance contemporary music. It would contain, Boulez explained, several small performance and rehearsal halls and would become an integral part of the Centre Pompidou — an avant-garde complex dedicated to the arts. The new complex was to be dedicated to Pompidou’s legacy. Boulez got what he wanted and accepted President Pompidou’s offer to come home to France and direct the institute. Boulez called his portion of the complex IRCAM — Institute Recherche Coordination Acoustic Musique [sic], and he designed a permanent office for himself. When I asked the maestro how he chose the name, he calmly explained that IRCAM could not be punned in any language.

Boulez’s role at IRCAM heralded a triumphant return to and investment in the contemporary music scene of Paris after his dramatic departure in 1959. In addition to his work at IRCAM, this investment involved conducting Paris’s Ensemble Intercontemporain, which Boulez co-founded in 1976, holding the chair of “Invention, technique et langage en musique” at the College de France (1976–95), and appearing in a six-part TV series called Boulez XXe siècle in 1988. Still, IRCAM took the majority of Boulez’s time and energy until he left in 1992, at which point he allocated more time to guest conducting.

The Ensemble Intercontemporain offered an all-Boulez concert in honor of their founder after his death in 2016.

Beginning in 1991, Boulez returned to Cleveland once or twice a season to lead projects and even went on tour with the Orchestra in 1993 (Carnegie Hall), 1996 (Paris), and 1999 (Carnegie). Boulez remained active internationally into the early 2000s, when health concerns began to slow — but by no means end — his musical activities. In the last decades of his life, he received countless awards for his composing, teaching, and conducting. In 2000, Boulez won the prestigious Grawemeyer Award for his chamber work sur Incises, premiered at the 1998 Edinburgh Festival. In 2009, he was named a laureate of the Kyoto Prize in the arts and philosophy category. In 2012, he was inducted into the Gramophone Hall of Fame. Here in Cleveland, the Musical Arts Association honored Boulez with the 2013–14 Distinguished Service Award, recognizing extraordinary service to The Cleveland Orchestra. Boulez also received the Glenn Gould Prize and Wolf Prize, numerous honorary doctorates, and many other awards.

Birthday Celebrations

For most composers, the birthdays and anniversaries that orchestras celebrate tend to come long after the honoree’s death. Before Boulez’s passing in 2016, however, The Cleveland Orchestra held three major birthday celebrations for him — for his 80th in 2005, his 85th in 2010, and his 90th in 2015 — the first two of which he himself conducted. As a happy coincidence, these celebrations also corresponded with the 40th, 45th, and 50th anniversaries of Boulez’s first appearance with the Orchestra in March 1965. Each of these programs featured quintessentially Boulez selections celebrating 20th-century music, including his own impactful compositions.

In April and May 2005, Boulez led three programs — two instrumental concerts featuring works by Webern, Stravinsky, and himself, and one operatic program featuring Stravinsky’s large-scale vocal works Les noces (The Wedding) and Le Rossignol (The Nightengale). The program book paid homage to Boulez’s impact on the Orchestra by featuring interviews with five musicians who joined at various points during his four-decade relationship with the group. All five agreed that Boulez was unflappable, funny, and comfortable to work with, all while demanding artistry of the highest order.

Listen to an excerpt of Les noces with Boulez conducting from May 7, 2005.

One of the foci of these interviews was Boulez’s unique conducting gestures, famously unimpeded by a baton. Principal Flutist Joshua Smith remarked, “He knows exactly how what he does with his hands affects the music. ... His use of his hands particularly is, I think, brilliant.” Smith’s colleague, then-Associate Principal Flutist John Rautenberg, focused on the precision of Boulez’s movements: “With these sparse movements of his hands and arms he can be so free with directing a rubato section. … It’s all with his hands. And it’s amazing how consistent and how good it is, and it’s always musical.” Cellist Catherina Meints agreed: “He can do things with his fingertips that show exactly where he wants the sound to happen. He plays the orchestra like anyone else plays an instrument.” “No one uses his hands the way Boulez uses his hands,” Principal Violist Robert Vernon continued, “He basically uses the fingers to give the lowest part of the beat. It is extremely clear.”

![Photos held in The Cleveland Orchestra Archives capture Pierre Boulez’s precision of gesture over the years. Franz Welser-Möst describes his “effortless control of the orchestra. You don’t see him [make] big movements … but it seems like all the strings between every single player and him are attached to his 10 fingers. And he does a little movement with one finger, and you get an explosion from one part of the orchestra.”](https://images.baskercdn.com/clevelandorchestra/media/boulez1_grid.jpg?w=600)

Boulez returned in 2008 to conduct two programs. Similar to 2005, one featured Second Viennese School composers (paired with J.S. Bach) while the second featured an operatic work, Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle. Two years later, he was back again for his 85th birthday celebration. For this concert, Boulez was joined by pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard, who, at age 19, had been a founding member of Boulez’s Paris-based chamber group Ensemble Intercontemporain. Boulez, Aimard, and the Orchestra recorded both of Ravel’s piano concertos during this special anniversary visit. The rest of the program included works by Messiaen — Boulez’s composition teacher — and Debussy, whose works Boulez recorded with Cleveland to great acclaim. The following week, Boulez led an all-Mahler program featuring the Adagio from Symphony No. 10 and Des Knaben Wunderhorn, which was also recorded.

Listen to the third movement of Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G Major, led by Boulez on February 4, 2010.

Boulez was scheduled to conduct large-scale opera projects again in 2012, 2013, and 2014, but his failing health led to the cancellation of all three engagements. Nevertheless, in 2015, the Orchestra threw a large celebration gala in honor of his 90th birthday. The 2015 program book perfectly captured the significant nature of Boulez’s time with The Cleveland Orchestra:

The special character of this ongoing relationship has been about his calm, friendly, and incisive manner as a musical tour guide, his way of re-exploring the well-known as well as discovering the unknown, and his open enthusiasm and understanding for doing so — both for the musicians on stage and for generations of audience members attending concerts at Severance Hall.

The concert interspersed video reminiscences with pieces by and significant to Boulez. The videos were combined into a single film upon his passing the following year.

Legacy

Pierre Boulez was — and remains — the conductor who maintained the longest working relationship with The Cleveland Orchestra. Since his first appearance in 1965, Boulez led the Orchestra in over 220 performances at home and on tour, and recorded more than 50 works with the ensemble, winning five Grammy Awards.

Enjoy the swirling climax of the Witches’ Sabbath from Boulez and the Orchestra’s Grammy-winning recording.

In 2015, Music Director, Franz Welser-Möst, reflected on the lasting impact Boulez has had on the reputation and identity of The Cleveland Orchestra:

I believe that Pierre Boulez has left his fingerprint on this Orchestra in a very strong way. He has conducted this orchestra [for] over 40 years with his very calm style of teaching the Orchestra the most complex scores. He has widened the horizon of all the players individually but also as a collective. … The Cleveland Orchestra in our day is known actually for playing the music, let’s say from the last 70 years, with an ease which is unmatched in our world, and I think that is very much thanks to him.

While Boulez had an indelible impact on the ensemble itself, he had perhaps an even deeper personal impact on the individuals he worked with here, as attested to by the musician interviews in the 2005 program book and 2015 videos. In pianist Joella Jones’s words, “We all love Pierre Boulez. I don’t know of any other conductor that, when he returns every time, when he walks out for the first rehearsal, just everyone is cheering and applauding and stamping their feet. … He probably has been the greatest musical influence on my life of anyone ever. He showed me that someone that brilliant can be so humble and down to earth, and I love him with all my heart.”

Joela Jones performed the solo piano version of Boulez’s Twelve Notations to open the 2015 celebration of Boulez’s 90th birthday, and the Orchestra played Boulez’s own orchestration of the work later in the evening. Listen to both versions of the second movement, “Trés vif.”

As much of an impact as Boulez had on the Orchestra and its members, his time in Cleveland was equally impactful on Boulez. It was in Cleveland, after all, that Boulez made his debut with a major US orchestra, and it was Szell who encouraged him to accept the ensuing offer of music director with the New York Philharmonic. After Szell’s death, Boulez reflected, “For me it was like a pupil and a teacher. This orchestra brought me [Szell’s] lessons.” On the Orchestra itself, Boulez reflected, “I was amazed by the homogeneity, by the attention they care to each other, by the intonation, by the exactitude of the rhythm. I rarely worked with an orchestra as attentive. When you say something, it was done and the next day it was also done.”

Looking back over Pierre Boulez’s life, it is overwhelming to take in all that he accomplished and all those he impacted. Neither the mathematically gifted adolescent entering the Paris Conservatoire in the middle of World War II, nor the firebrand modernist leaving the Conservatoire behind for more experimental environments could have imagined the international impact he would have as a conductor and pedagogue, nor the immense role that a city in Ohio would have in that career. It seems somehow fitting to close this essay with Boulez’s own metaphorical words, one of the same quotations that helped introduce him to American audiences in 1965:

Music is a way of being in the world, becomes an integral part of existence, is inseparably connected with it; it is an ethical category, no longer a merely aesthetic one. … Imagination will have no difficulty if technique does its share. Moreover, a composer enjoys setting out toward a certain horizon and arriving in completely unknown countries, whose existence he hardly suspected at the beginning.

— Ellen Sauer Tanyeri was the 2024–25 season archives research fellow. The fellowship is an opportunity for graduate music students from Case Western Reserve University to work with The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.