A Twist on a Holiday Favorite: Handel’s Messiah and The Cleveland Orchestra

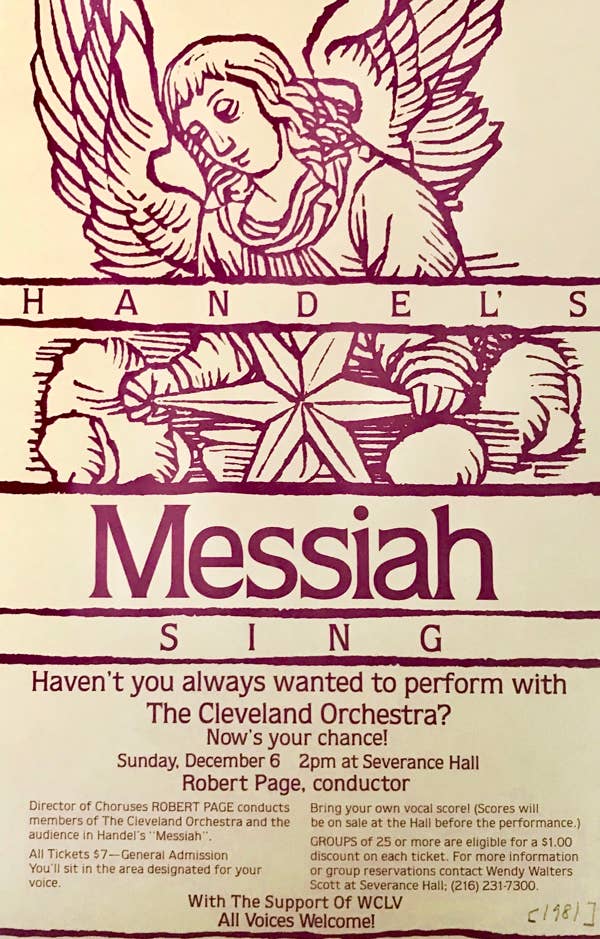

“Have you always secretly wanted to perform with The Cleveland Orchestra?” read the headline of a 1974 Plain Dealer article announcing Page’s plans to put on a sing-along of Handel's iconic holiday work, a tradition carried on until 1984.

The Cleveland Orchestra and Chorus’s first full performance of Handel’s Messiah happened in December 1965, and was conducted by Robert Shaw, the legendary American choral composer and associate conductor of The Cleveland Orchestra and Chorus. The performance was notable for presenting an interpretation of the piece similar to how it would have sounded back in Handel’s day. Shaw molded the Orchestra and Chorus’s sound to create a leaner, clearer, and more brisk performance than that of the orthodox interpretation, which used huge performing forces and slower tempi to create a veritable wall of sound. While reviews of the performance were mixed, Shaw’s interpretation of Messiah was incredibly influential, and contributed to an overall change in how many orchestras and choruses perform this piece today.

“For Unto Us a Child is Born,” excerpt from Messiah by George Fredric Handel. The Cleveland Orchestra and The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus, Robert Shaw conducting, December 4, 1965.

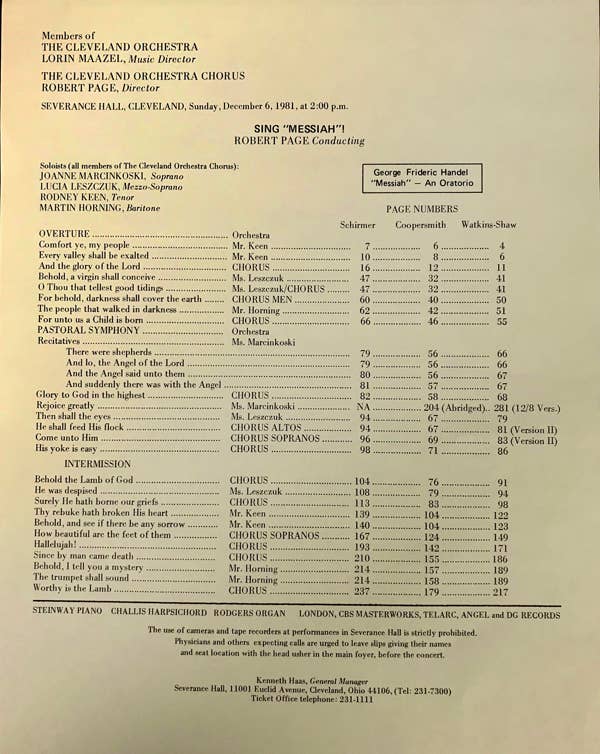

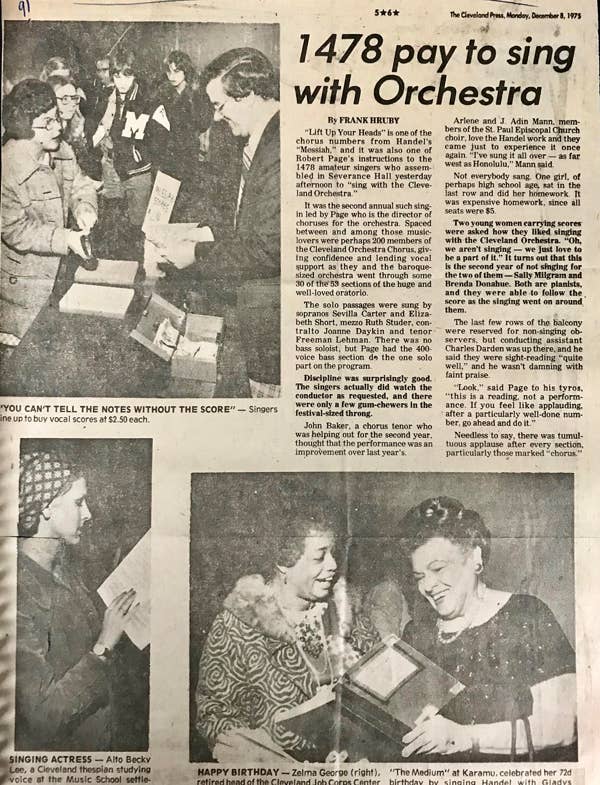

In 1974, The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus Director Robert Page (1927–2016) invited attendees to joining in singing the famous oratorio from their seats. “Have you always secretly wanted to perform with The Cleveland Orchestra?” read the headline of a 1974 Plain Dealer article announcing Page’s plans to put on a sing-along of the iconic holiday work, a tradition carried on until 1984. Scores could be purchased at the door, but for those who had brought their own, five dollars bought boasting rights for participating in a Severance Hall performance with The Cleveland Orchestra.

Some critics were skeptical of the project, nervous that a thousand-some untrained voices would make for a less-than-musical performance. “Why not leave it to the pros?” asked one Plain Dealer critic. For Page, though, the sing-along wasn’t about putting out a pristine product, but about lifting the veil between stage and audience, a campaign central to his career. “Amateur singing is alive and well. And I’ll take as many voices as I can get” he told The Plain Dealer in 1974. Obituaries remembered Page as much as a vanguard of classical music accessibility as for carrying the chorus into its “golden age.”

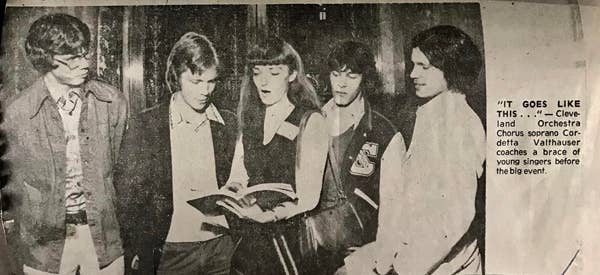

For Page, inclusivity didn’t mean technical laxity: “Page is a hard taskmaster, a perfectionist, and the chorus loves him for it,” one member told The Cleveland Press. And he exerted his dramatic coaching style and critical ear no less on the tyros of his sing-along forces. One participant recalled his insistent gestures for vowel shapes and whole-body engagement. But, again, for Page, technical improvements weren’t an end in themselves but about the experience of engaging in meaningful performance. He understood the irresistible lure of voices in harmony and capitalized on it: “Everybody can sing. God gave us all voices and there’s an excitement in the sound of one human voice singing with another human voice,” Page told a reporter for The Plain Dealer in 1979.

By all accounts, Page’s eager masses impressed. One reviewer for The Cleveland Press wrote that “discipline was surprisingly good! The singers actually watched the conductor as requested, and there were only a few gum-chewers in the audience.” More importantly, Page’s vision of engaging the audience in something more than a sing-along was a success. One participant recalled that after the final note of the famous “Hallelujah” chorus, a silence fell over the hall as participants basked in a palpable sense of pride. “Look,” Page broke the silence, “this is a reading, not a performance. If you feel like applauding after a particularly well-done number, go ahead and do it.” Applause erupted.

— Michael Quinn was the 2018–19 season archives research fellow. The fellowship is an opportunity for graduate music students from Case Western Reserve University to work with The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

Want to know more?

The Lives of the Great Composers (Chapter III: Composer and Impresario, George Frederic Handel), by Harold C Schonberg: Idiosyncratic but fascinating biographical portrait of Handel.

Handel’s Last Chance, 1996: A children’s movie telling a fictionalized story of the composition of Handel’s Messiah, and an unlikely friendship between the composer and a young boy singer lifted out of poverty.

Hallelujah! and Other Great Sacred Choruses, Robert Shaw conducting The Cleveland Orchestra and Chorus, BMG 2000.