A Musical Treasure Chest: The History the Norton Memorial Organ

Many of us are familiar with the rich legacy of Severance Hall, built in 1931 as the home of The Cleveland Orchestra. But you might be surprised to find out that Severance Hall’s symphonic organ, known as the Norton Memorial Organ, has quite a history of its own as well.

This feature incorporates earlier articles on the Norton Memorial Organ by Kate Rogers (2014–15 Archives fellow), Sophie Benn (2016–17 Archives fellow), and Kevin McBrien, Cleveland Orchestra Publications Manager.

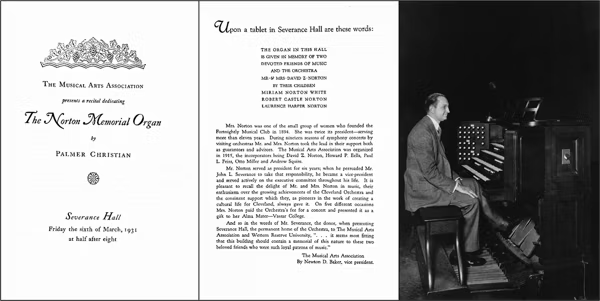

Well into its ninth decade, the Norton Memorial Organ proudly stands as one of the finest orchestral organs in the country and is enjoyed year-round during orchestra concerts, film screenings, and solo recitals. This instrument, named in memory of David Zadlock Norton and his wife Mary Castle Norton, was procured with a $60,000 gift from their children, Miriam White, Robert Norton, and Laurence Norton, at the time that Severance was built.

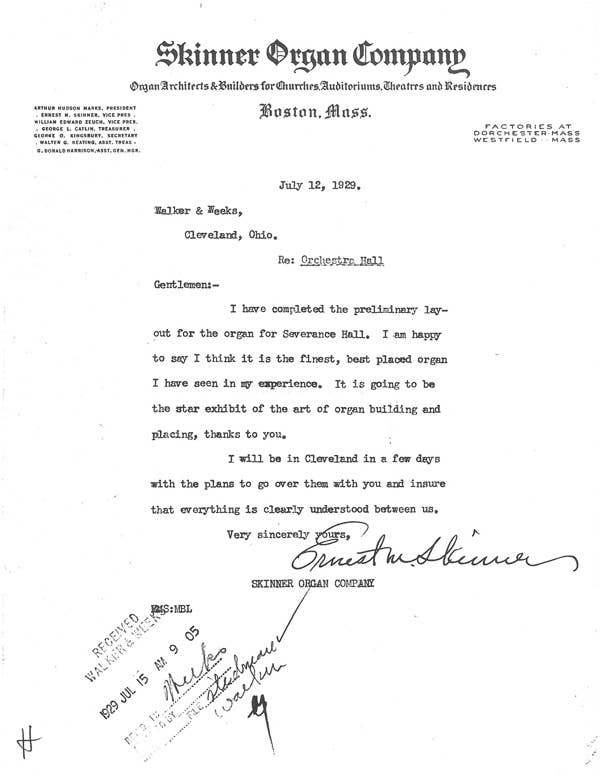

Designed and assembled in 1930 by renowned organ maker Ernest M. Skinner and his Boston company, this magnificent instrument is one of the largest Skinner organs in existence. It weighs 50,000 tons, comprising 94 ranks of 6,025 pipes ranging in length from 32 feet to a mere 8 inches.

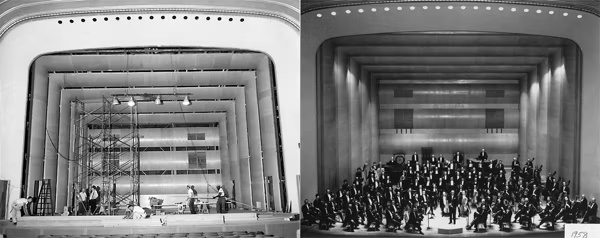

The location of the organ in Severance Music Center is hugely important for its sound. Its original installation, in a cramped space above the stage, made the organ difficult to hear. When the hall was designed in the late 1920s, every consideration was taken to make it as comfortable, beautiful, and acoustically resonant as possible. Architects Walker & Weeks — with input from Skinner and Case Institute acoustician Dayton C. Miller — decided to house the Norton Memorial Organ in a space above the stage:

A 1930 press release describes the acoustic vision behind this placement:

Through the extraordinary cooperation of Walker and Weeks, the architects, the organ has been given a location almost without precedent. It is to be placed directly over the orchestra, in a concealed position, with sound reflectors which will unite the tone of the organ with that of the orchestra, when they are used together.

The tone will enter the auditorium through a grille placed directly over the front of the stage. The effect of the sound reflectors will be to give the same result as though the organ were below the ceiling within the auditorium itself. In spite of this fact the position above the ceiling will lend a charm and touch of mystery that will greatly enhance its musical character.

Alas, it turned out to be a flawed plan. After the solo recital dedicating the instrument in March 1931, audiences began to notice that the sound of the organ left much to be desired.

Unfortunately, no documented recordings of the organ exist in its original position to give us a sense of this muffled quality. We have only rich descriptions from newspaper reviews like the one below to offer a sonic picture of this era.

In 1932, a review in the Cleveland Plain Dealer noted the organ’s unsatisfactory sound during Handel’s Organ Concerto in F Major: “Carl Weinrich was the organist of the evening. […] but with all his skill and resource he was playing a losing game, for the organ, save now and then, seemed an adjunct to the orchestra.” Of the encore, a J.S. Bach prelude and fugue, the reviewer added: “I missed a certain clarity and roundness of tone in the beginning of the prelude and in the announcement of the fugue theme; though whether this was due to the location of the organ boxes, I am unable to say.”

Rather than taking immediate action to make this beautiful instrument fully audible, the massive organ was left as-is. Further modifications to the Severance stage only further muffled the sound of the organ. In 1958, under the leadership of Music Director George Szell, a new state-of-the-art acoustic shell was installed on the stage. This addition, the “Szell Shell” as it was affectionately dubbed, was designed to improve the sound of the orchestra, but it blocked off the tone opening for the organ, effectively entombing the instrument.

This April 1967 recording of Camille Saint-Saëns’s “Organ” Symphony with conductor Georges Prêtre and organist David Goodling is an example of the balance of the post “Szell Shell” organ. Mid-century recording technology does not fully capture the disconnect between live orchestral sound and semi-amplified organ sound.

Satisfied with how well the “Szell Shell” enhanced the hall’s acoustics, engineers bypassed the problems it created by amplifying the organ through speakers. This modified sound worked but was still less than ideal for the magnificent instrument. Because of these unsatisfactory conditions, the organ was used only sporadically during the Szell years and laid dormant after 1976.

Performances of Hector Berlioz’s Te Deum in April 1976 marked the last time the Norton Memorial Organ was used in the “Szell Shell” era. The organ, played by Joela Jones, can be heard in the opening bars, clearly underbalanced with the orchestra’s magnificent volume. Compare this recording with the 2002 recording of this same piece, later in this story.

During his tenure as music director (1984–2000), Christoph von Dohnányi felt the Orchestra deserved a working organ, and that the organ deserved a better position within the hall. With hopes of finally reclaiming the organ’s voice, the Severance renovations of 2000 included several measures to improve conditions for the long-sequestered instrument.

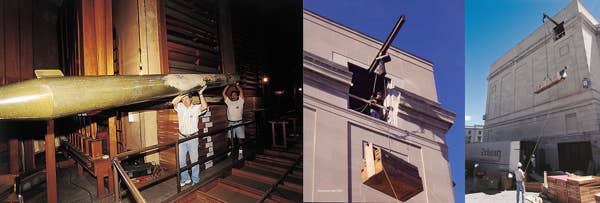

First, the organ chambers were relocated to a purpose-built space directly behind, rather than above, the stage.

The new hall design also included three impressive ranks of façade pipes built into the stage. Anyone attending a concert in the past two decades might assume that organ pipes lining the back wall of the main stage are part of the instrument, but these pipes, like the pipes on the walls of many symphony orchestra halls, are what are called façade pipes. These “just-for-show” pipes serve several important purposes. First, they are more aesthetically pleasing because they can be symmetrical, unlike the uneven lengths and varied materials of functioning organ pipes. They also protect the real organ pipes from damage and, most importantly for the long-muffled Norton Memorial Organ, they provide a porous surface through which the organ’s sound can easily project into the concert hall.

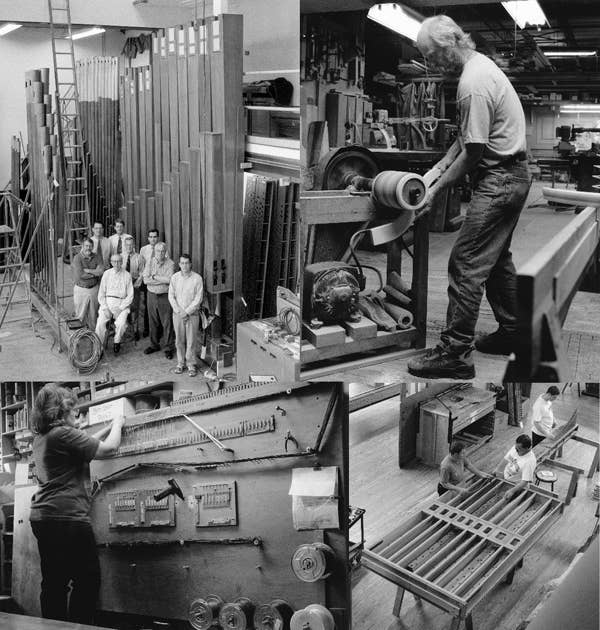

While the hall got its facelift, the organ itself was whisked off to the Schantz Organ Company in Orrville, Ohio. All the organ’s pipes and mechanism had to be carefully removed and reinstalled during this process. Those pipes small enough to fit through the foyer doors were removed by hand prior to the renovation, while the largest organ pipes and wind chests were meticulously extracted from the organ chamber using a crane.

The organ remained in Orville from July 1997 until June 2000. During this time, the organ was carefully restored, and new pipes were built for the façade. This multi-year process was documented by local photographer Jennie Jones, whose prints now live in The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

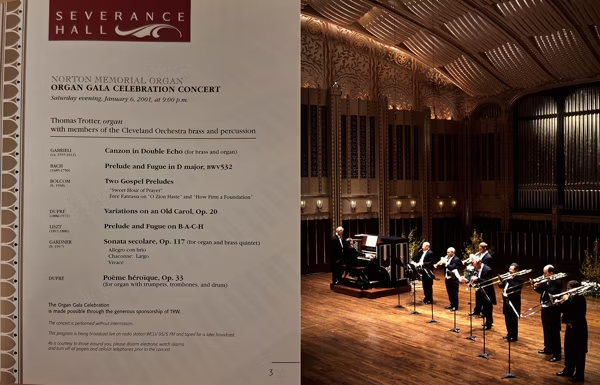

The organ was installed in its new home behind the renovated stage in 2000, and a gala re-dedication recital for the organ was held on January 6, 2001, featuring Thomas Trotter and members of the Orchestra’s brass and percussion sections.

The organ sounds glorious in this recording of Thomas Trotter playing Franz Liszt’s Prelude and Fugue on B-A-C-H from the rededication gala in 2001.

Upon its rededication, the organ was immediately put to good use. The week after the dedication, Joella Jones joined Resident Conductor Jahja Ling for Saint-Saëns’s “Organ” Symphony. The organ was featured heavily that same month in the 2001 Martin Luther King, Jr. concert. In February, the Saint-Saëns was revisited for a series of education concerts, and yet again on May 31 and June 1 for two special “Organ Spectacular” concerts (underwritten by the Shantz Organ Company) which also featured Todd Wilson playing Joseph Jongen’s Symphonie Concertante for Organ and Orchestra, Op. 81.

The organ was on full display in performances of Saint-Saëns’s “Organ” Symphony. Joela Jones joins Jahja Ling and the Cleveland Orchestra in this January 2001 live concert recording.

After a summer away at Blossom, the Orchestra returned to Severance for another organ-filled season in 2001–02. Robert Porco led four concerts in the last week of October featuring Joela Jones playing the restored instrument in James MacMillan’s Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis for chorus and organ, and Francis Poulenc’s Concerto for Organ, String Orchestra, and Timpani. On December 23, a special holiday organ and brass concert capped the first calendar year of the Norton Memorial Organ’s triumphant return. Two months later, Jones played Berlioz’s Te Deum, a poignant counterpoint to her performance in the organ’s final concert from 1976.

A recording of Berlioz’s Te Deum with Joela Jones and Christoph von Dohnányi from February 2002 provides a dramatic contrast with the recording of the same piece from 1976 (featured earlier in this essay). In the 1976 recording, with the organ trapped above the stage, the organ sounds half as loud as the orchestra as they trade off chords in the opening. In this recording, the restored and relocated instrument is even louder than the combined orchestral forces.

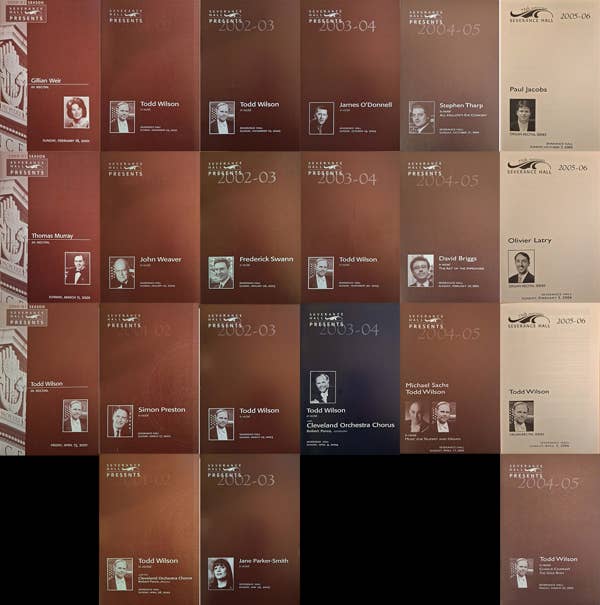

The organ restoration also marked the beginning of an ongoing organ recital series in Severance that ran through the 2005–06 season. The first several concerts were sponsored by Schrantz, while later iterations were considered chamber recitals. These performances included a broad range of organ soloists and repertoire, including improvised soundtracks to silent films.

Even after its triumphant return in 2001, however, the Norton Memorial Organ continued to be plagued by problems.

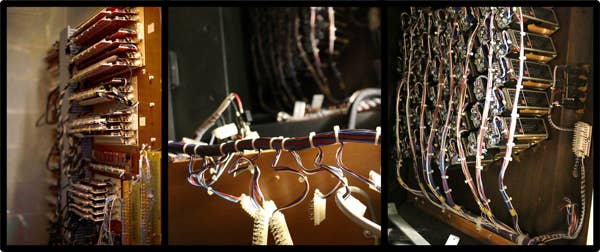

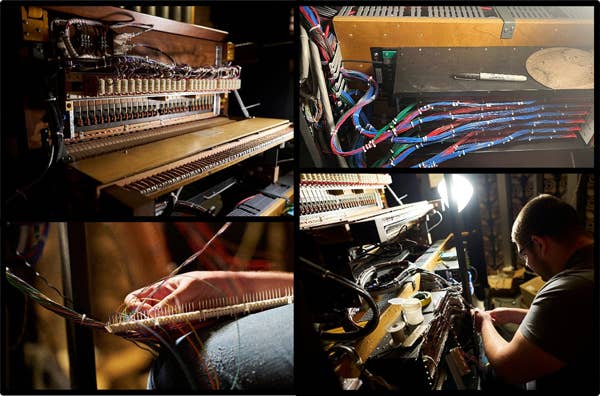

The most notorious stemmed from the 32-pin plugs which connected the console (keyboard) to the instrument’s 6,025 pipes in the organ loft. These plugs (the same kind of cables once used in World War II bombers!) were so finicky that stagehands created elaborate plans to avoid moving the organ console during performances. Production Manager Ian Mercer even took to keeping an organ technician on hand in the event of “TOF” — total organ failure.

Luckily for paying audiences — and Mercer’s health — TOF never materialized. Now, thanks to an electrical overhaul conducted in 2023, it never will. Ms. Ginger Warner and Mrs. Frances Buchholzer made generous contributions in memory of Mr. William P. Blair III, a longtime patron and Orchestra volunteer, to provide state-of-the-art upgrades for the organ.

The upgrades were again entrusted to the Schantz Organ Company and took place in summer 2023 while the Orchestra was away at Blossom Music Center. The priority was to replace the old 32-pin plugs with much faster and more reliable ethernet cables, but this was far more than just a rewiring project.

The organ console received a new set of keyboards with smoother action and digital enhancements, allowing performers to switch keyboard functions depending on their preference. (The location of the primary keyboard often differs between countries — it is typically on the bottom in France and the middle in England and the United States). Performers have even more control over the sound through the pistons between the keyboards, which access pre-programmed sounds. The 2023 refurbishments increased the number of pistons by 50 percent, now offering performers 12 pre-set options.

As any organist will tell you, the foot pedals are as important as the keyboards. A new pedal divide feature splits each of the 32 pedals so that the lower pedals (played by the left foot) can intone bass notes, while the upper pedals (played by the right foot) can sing a melody using a completely different sound. Similar to the sustain pedal on a piano, a new switch near the pedals creates a sostenuto effect to hold a note underneath other moving lines.

Finally, a drawer on the right side of the console reveals a treasure trove of new tools. Controls allow individual organists to label and save unique combinations of stops (the sounds and effects created by the rows of knobs around the console), and a sequencer helps them advance through these combinations. The drawer also includes a transposer button to move pitches to any key.

The organ project was highlighted the following year in the fall edition of The Cleveland Orchestra’s Spotlight magazine, but this set of improvements did not usher in the same flurry of organ features as the much larger 2001 restoration had. In the organ’s first solo feature since the refurbishments, James McVinnie transformed Severance into a living ecosystem in his rendition of Gabriella Smith’s Breathing Forests in April 2024.

The Norton Memorial Organ shines through the lively orchestral texture in the opening of Smith’s Breathing Forests.

Despite being tragically underappreciated and deprioritized throughout its long life, the Norton Memorial Organ is now fully equipped to dazzle audiences at its brilliant full potential and will continue to do so in small and large ways for generations to come.

— Ellen Sauer Tanyeri was the 2024–25 season archives research fellow. The fellowship is an opportunity for graduate music students from Case Western Reserve University to work with The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.