A Signature is Worth a Thousand Words: The Cleveland Orchestra’s Guest Artist Autograph Book

Deep within the archives of The Cleveland Orchestra lies a set of large, unassuming books — until you open them, that is, and find a collection of signatures, messages, and illustrations by many of the leading musicians of the past century.

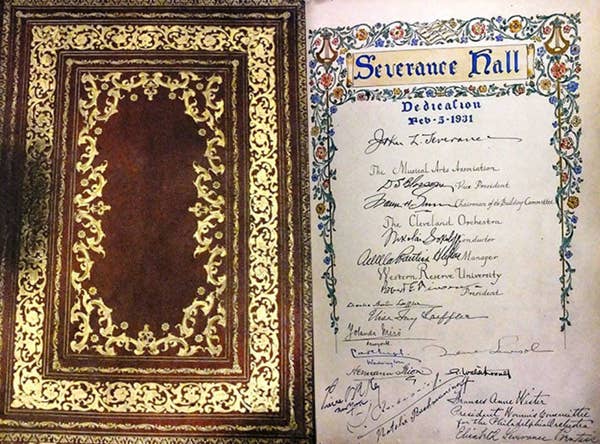

Deep within the archives of The Cleveland Orchestra lies a set of large, unassuming books — until you open them, that is, and find a collection of signatures, messages, and illustrations by many of the leading musicians of the past century. Since their inaugural concert at the newly built Severance Hall on February 5, 1931, the Orchestra has asked its guest performers, conductors and lecturers to sign an autograph book. Leafing through the pages of any one of these books is an amazing and personal look back through musical history.

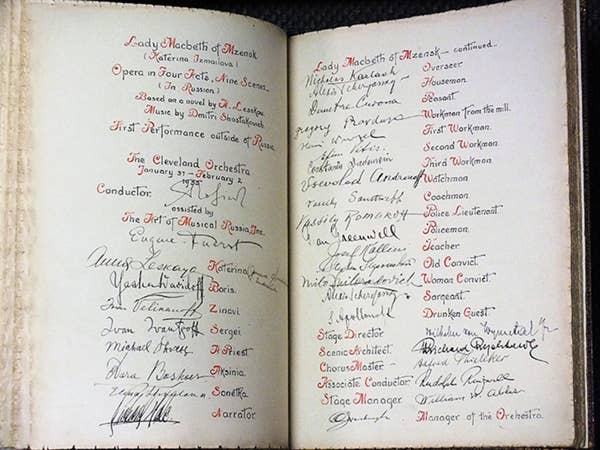

In particular, the Orchestra’s performance history of opera is well-documented in the guest artist autograph book. Under the direction of Artur Rodziński (1933–1943), The Cleveland Orchestra began to frequently present fully staged opera productions, starting with Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde on December 14, 1933. Perhaps the most famous was the premiere of Dmitri Shostakovich’s controversial 1933 opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk in 1935. This production was the first outside of Russia, and was one of the few opportunities to see the opera outside of Russia before its censoring by Stalin in 1936, whereupon it became unavailable for over 35 years.

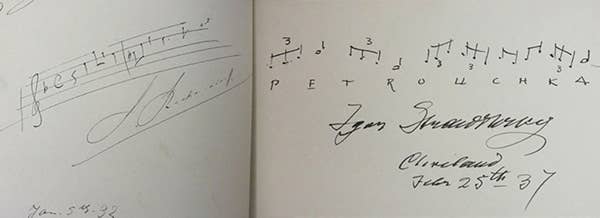

Many of the leading composers, performers and conductors of the day signed the guest book. One such was Sergei Rachmaninoff, the composer and pianist, who was one of the more prolific signatories during the guest book’s early years. His autographs were large and featured an excerpt of whichever piece of his he had played with the Orchestra earlier that evening. Another was Igor Stravinsky, one of the major composers of the 20th century, who visited Severance Hall on February 25, 1937 to conduct several of his pieces. Stravinsky’s autograph includes the signature rhythms of the living puppet Petrushka from the eponymous 1911 ballet.

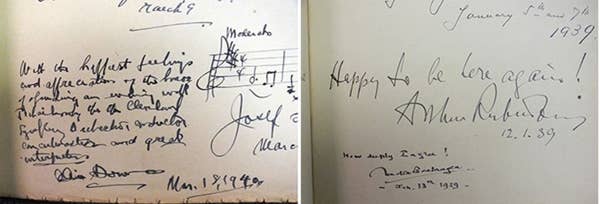

Other guest artists wrote longer inscriptions, or responded to past comments. Olin Downes, the long-running music critic of the New York Times wrote a particularly effusive message to The Cleveland Orchestra after an emotional experience attending a March 18, 1940 performance which featured Tchaikovsky’s first violin concerto. Others, like Nadia Boulanger, a French composer and pedagogue teacher whose pupils included Aaron Copland and Quincy Jones, succinctly expressed her feelings through responding to a guest of the prior evening, the Polish American pianist Arthur Rubinstein.

The guest artist autograph book is a living tradition of The Cleveland Orchestra. Each year, more and more signatures, illustrations, and inscriptions are added. Looking at any single page is like stepping back in time and getting a glimpse at the moment when the life of any one musician crossed with that of the Orchestra. A signature really can be worth a thousand words.

— Alex Lawler was the 2015–16 season archives research fellow. The fellowship is an opportunity for graduate music students from Case Western Reserve University to work with The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

All photographs and audio clips courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.