Louis Lane at 100: The Orchestra’s Unsung Matinee Idol

A digital remastering of his Columbia discography reminds us that Louis Lane’s quarter-century with The Cleveland Orchestra contained multitudes

As a musician, nothing that I thought would happen to me has ever happened; however, to my immense surprise, many very nice things have happened.

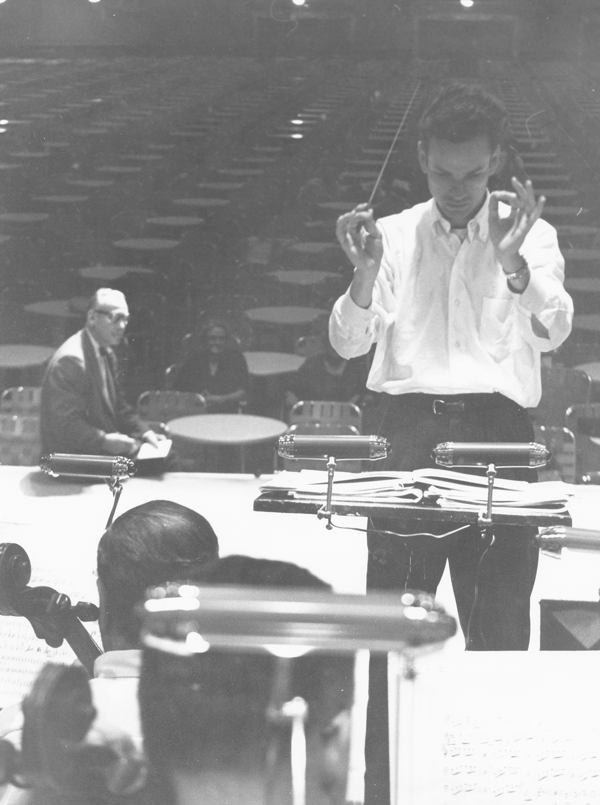

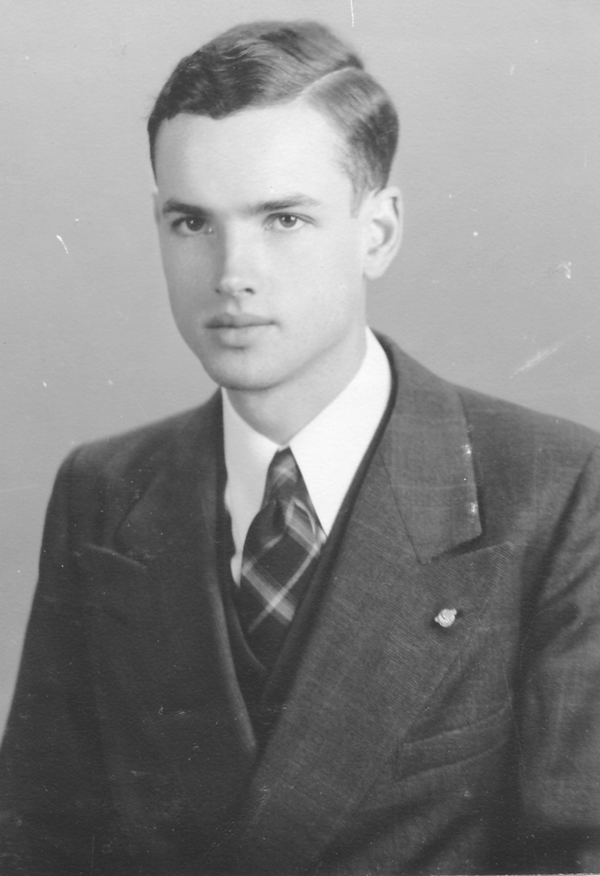

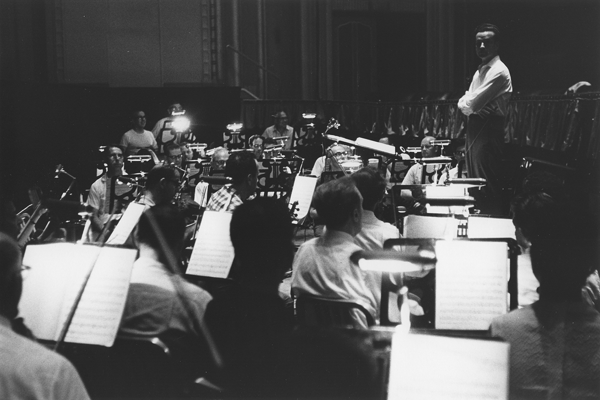

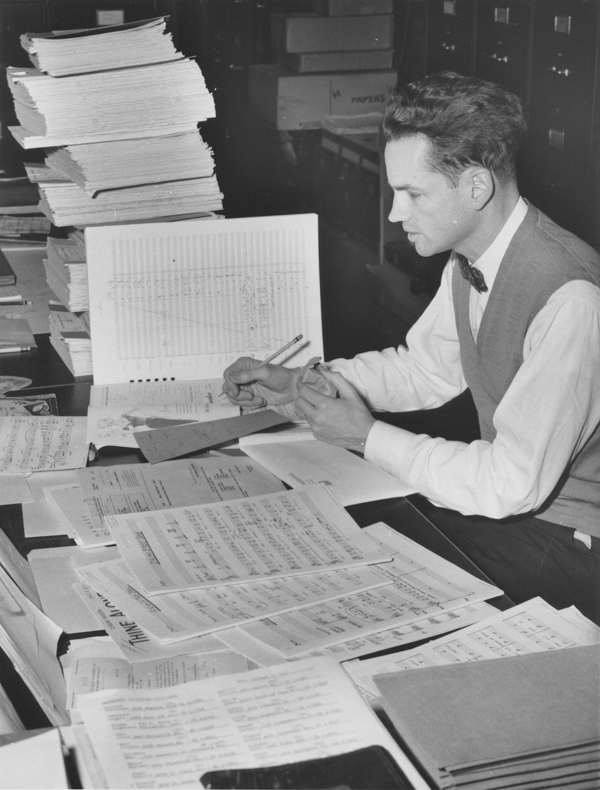

The pictures tell only part of the story, entrancing us even as they sometimes unintentionally mislead. Over the years, the Cleveland Orchestra’s archives have curated a sprawling collection of official and semi-official photographs, which provide one of the most vivid proofs of the ensemble’s development — second only to sound recordings, perhaps. Among these are myriad images of the Orchestra’s conductors: principals and assistants, formally or informally attired, posed or caught spontaneously, often at the podium, baton in hand. These collected images make a special appeal for the memory of one of the ensemble’s more unsung heroes, who holds a singular cachet in its annals as something like a career assistant conductor. As it turns out, Louis Lane, who died in 2016 at the age of 92, was the furthest thing from an also-ran.

If anything, Lane’s steady, modest-minded career is sobering proof that neither talent, industry, nor even — in his case — beauty is entirely sufficient to attain lasting fame as a conductor. Throughout his long career, Lane received the kinds of glowing reviews that more overtly ambitious conductors might have killed for. Yet, unlike those podium-climbers, Lane always seemed more concerned with the day-to-day exigencies of score preparation and rehearsal than with career advancement. It wasn’t shyness or false modesty. Knowing that he couldn’t reasonably hope to be granted the directorship of another among America’s “Big Five” orchestras, or even among its top 10, he decided to stick with his well-honed role as second fiddle. He surely couldn’t have known that, in choosing to anchor his career, more or less permanently, in Cleveland, he would arguably become the most persistent podium presence the Orchestra has ever enjoyed.

By the time of George Szell’s death in 1970, Lane was long-entrenched with the Clevelanders (he would ultimately eclipse Szell’s record 24-year tenure with the ensemble by two years: Lane was with the Orchestra from 1947 to 1973). More than any of Szell’s other Cleveland protégés, he could claim a special dispensation from that titanic maestro. When Szell began auditioning and accepting assistant conductors in the late 1940s, Lane was one of the earliest brought on board. He’d been studying composition at The Eastman School in Rochester, following his discharge from the army after the Allied victory in 1945. Lane later recalled that, at age 22, he “noticed that there was on the bulletin board [at Eastman] a flier announcing an apprentice conductorship with The Cleveland Orchestra.” He auditioned and was essentially told to stay in school and continue studying — they would contact him when they were ready.

He must have been sufficiently memorable to have prompted Szell to follow through on scheduling a subsequent audition. Not overly experienced in conducting, Lane selected an obscurity from among the Mozart symphonies, No. 28, reasoning that he’d stand a better chance if Szell were unfamiliar with his audition piece. (The two of them laughed over his strategy when he confessed it during his audition, a scene that augured an unusually collegial rapport between Szell and an underling.) Lane came to Cleveland in 1947 and made himself quietly indispensable to the Orchestra’s life during the 1950s and ’60s, first as a keyboardist and percussionist, and then, only gradually, as a conductor. Szell’s conception of the Orchestra’s assistant conductorships was, at base, an indentureship whereby young conductors were permitted to regularly observe his own conducting in rehearsals while also assisting the Orchestra in other capacities, in exchange for a rather modest yearly stipend provided by noted local benefactors, the Kulases. Lane recalled Szell’s saying, “I’m ready to answer a serious question at any time, but there will be no lessons. I believe that you can learn from watching me and listening to the orchestra. If not, I’ve made a bad mistake.”

The arrangement was not, in fact, so exploitative as it might sound. Szell was a noted drill sergeant on the podium, and his rehearsals were thus packed with vivid, concrete directives that were an object lesson in musicianship (and leadership) for budding conductors. Lane later recalled Leopold Stokowski’s rehearsals with the Orchestra as a guest conductor, during which phenomenal musical effects were achieved in a manner quite different from Szell’s: minimal verbal instruction punctuated Stokowski’s famously idiosyncratic physical technique of reformulating the ensemble’s sound (typically conducting sans baton ); with Stokowski, “It was all a question of gestures,” Lane said. Whatever the effectiveness of these disparate conducting styles for Szell and Stokowski, the former’s approach surely provided more substantial possibilities for education via observation. As Szell predicted, a disinclination to give actual conducting lessons seems not to have prevented his acolytes from gleaning compelling insights from his example. And there has been a general concurrence that Lane, as much or more than any other of Szell’s protégés, inspired a special affection and respect from this fearsome mentor.

Lane remarked, years later, that his own youthful unsophistication gave rise sometimes to a casual assertiveness during his early interactions with Szell, which the maestro actually found more palatable than the cowering of other assistants who knew enough to be overawed by him. Seymour Lipkin, Lane’s counterpart during his first year with the Orchestra (later a famous pianist-pedagogue), was easily his superior in knowledge and experience at the time, per Lane, but was nonetheless dumbstruck by Lane’s willingness to politely but firmly contradict Szell when he felt justified in doing so. It’s doubtful, however, that many of the staff or musicians who came to the Orchestra later, during Lane’s halcyon days with the organization in the 1960s, would have recognized this younger version of the authoritative, middle-aged Lane they knew. If anything, Lane is remembered today for his remarkably mature and technically accomplished musicianship.

His early education was far more than merely adequate — still, he must have remained an inveterate autodidact all through the 1950s and ’60s, in order to have attained his eventual professional command. I spoke with Joela Jones, the Orchestra’s pianist emerita, only recently retired after a half-century stint with the ensemble, who recalled the great stock that Szell put in Lane. During rehearsal, Szell sometimes gave the podium over to Lane so that he could “go out in the hall and have Louis conducting almost complete movements of something that [Szell] was going to perform and conduct … he wanted to hear how it sounded in the hall. And I’ve always wondered why other conductors didn’t do that more,” Jones says. Similarly, she observed Lane acting as Szell’s “right hand man” during recording sessions as technical details were worked out in the sound booth. It was Lane upon whom Szell thoroughly depended to ensure that his ideas were carried out by the sound engineers. “That shows how great Louis really was.”

Jones stressed the fact of Lane’s conspicuous intelligence — and she is not alone in highlighting this point. Moreover, she and others tend to emphasize that Lane’s intellect was intrinsic to his artistry. “He was very academic, professorial at rehearsals” — exceptionally taxing (another common characterization of him) — and it wasn’t really until the performance that the full scope of his vision was revealed, as he permitted the more natural, instinctive side of his musical personality to shine through. In rehearsal, Jones says, “I don’t think Louis talked about emotions a lot. But that doesn’t mean he didn’t feel the emotions.” Though he never conducted nearly as many of the regular season concerts as Szell (except, perhaps, for a brief time in the early 1970s, when he acted as Resident Conductor), Lane did lead many programs — including education and pops concerts — which formed a significant part of the local concert life, and should not be casually diminished in a historical recounting of the Orchestra’s development.

Indeed, it was these ancillary initiatives that Jones applauds as among his more irreplaceable bequests to the Orchestra and the city. She noted, also, his crucial advocacy for ensemble’s musicians in the mid-1960s push for stable, year-round work. Up until that point, it was not unheard of to find various members moonlighting as haberdashers or grocery employees, for example, to make up for the lack of a full-time salary. Lane was the primary advocate, Jones says, for full-time orchestral employment with commensurate pay — no small order, given the considerable expense of transforming a 100-piece seasonal orchestra into a salaried workforce. Lane recalled the musicians’ earlier discomfiture, during the uncharacteristic summer of 1953, when renovations to Cleveland’s Public Auditorium normally used for summer concerts (for which they were billed as the “Summer Orchestra”) obliged them to move out-of-doors, into the old Cleveland Stadium, home of the Cleveland Indians (now the Guardians). “It was quite an effort on my part to find music that was loud most of the time,” Lane recalled. “We played a lot of marches and a few waltzes. … A lot of stuff which I hope we won’t have to play again.” Of the audience at these events, he observed, “I think they were amused and it was like an audible hot dog.”

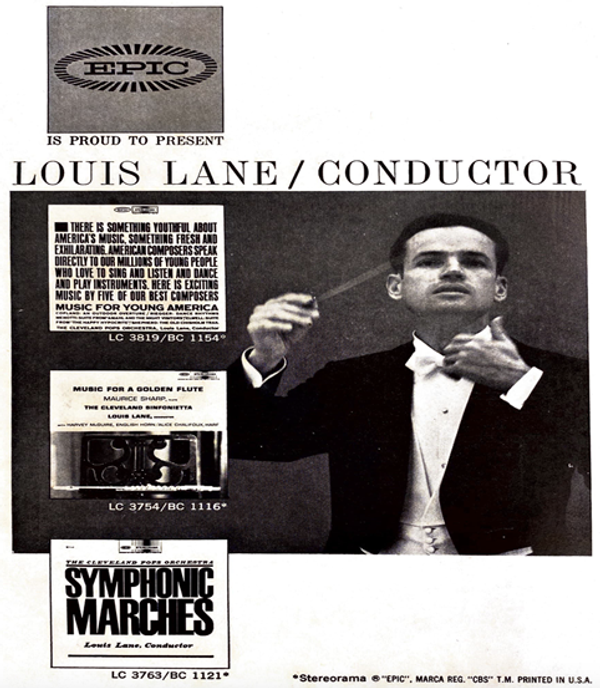

Recording opportunities arose in the wake of the Orchestra’s fabled European tour of 1957 — and Lane himself would conduct important concerts during the 1965 tour. (“Many of the Europeans had never heard of Cleveland,” Lane recalled. “Of course they had heard of New York and Chicago and Philadelphia and Washington, but they had never heard of Cleveland. So the fact that the orchestra was so good was a surprise.”) The Orchestra’s triumph abroad led to Columbia Records’s renewed interest in the ensemble’s recording contract, and in the possibility of using a Columbia sub-label, Epic, for which Lane began recording albums in 1959 with the Cleveland Pops Orchestra (effectively the Summer Orchestra, and therefore a de facto derivative of The Cleveland Orchestra). Lane recalled that Columbia had

wanted to do more albums a season than Mr. Szell was willing to do. Somehow Beverly Barksdale [the Orchestra’s manager during this period] thought that if we picked the right repertoire we could set up a Cleveland Pops series to rival the Boston Pops series. Well, … it never worked out that way. But that was the plan at the beginning.

Lane might have been writing his own epitaph: That was the plan in the beginning, but it never worked out that way …

Born in 1923, in a border town — Eagle Pass, Texas — Lane’s childhood environs seem quite unlikely as the incubator for a major musician. His early musical development he credited to a neighbor, Lupita Hume, an accomplished pianist who determined that the 5-year-old Lane merited particular solicitude: He would trot over to her house for supervised practice (followed by ice cream) five days a week as a child. Lane was early to college, at UT Austin, where he studied music, graduating at the tender age of 19, after which he served in the Second World War for three years in the European theatre.

The war, he observed, made for “almost a complete break” in his musical activities:

It was not very conducive. It was appropriate in a way, however, because I was in the field artillery. And when I came back here when I eventually became a member of The Cleveland Orchestra, I was assigned at first to playing the bass drum.

Upon returning stateside, he attended Eastman for graduate studies in composition, though he would later claim that a brief summer stint of compositional study under Bohuslav Martinů at Tanglewood was far more significant to his development. (Lane regarded Szell and Martinů as his two teachers of significance.) His old piano teacher, Mrs. Hume, observed (from afar) some of Lane’s greatest successes, which had taken him a long way from his birthplace.

In 1970, after more than two decades spent diligently tilling the fields as an assistant to Szell, Lane was appointed as essentially the Orchestra’s conductor regent for the two years following Szell’s death, in an unexpected career-capper worthy of the-tortoise-and-the-hare. No one could seriously have doubted his qualifications as custodian during the search for a new, permanent music director of international stature. Despite receiving consistently fine reviews for performances with a variety of orchestras in various cities over the years, Lane never quite achieved a truly international reputation; and it is difficult to infer any particular reason that he should not have done. (One can encounter more privately expressed reservations regarding his imaginative capacities as an interpreter, but such critiques must be weighed against Lane’s remarkably robust track record with the national press, including some high-stakes performance situations in which a more meager talent would surely have been stymied.) It is not so very hard to imagine a counterfactual history in which, the difficult search for a new music director having foundered, Lane himself accedes the role of music director. Far from suffering for lack of a star at the helm, it seems likely, given Lane’s evident capabilities, that the Orchestra would, in a short time, have conferred its status upon a conductor who, in addition to a formidable musicianship, had sported the unquantifiable PR benefit of looking like a golden-age Hollywood contract player.

The plain fact of the matter is that, to judge from both musicians’ recollections and press clippings, Lane was a rock-solid conductor, with an astonishingly wide range of repertoire (wider, in everyday practice, than Szell’s). Lane’s extreme ease in toggling between diverse musical styles was probably a professional liability in some respects: What do you make of a conductor who seems equally at home in a Blossom concert medley of Lerner & Loewe tunes and the Cleveland premiere of Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie? Lane was known for both: his skill and sense of comfort when leading the orchestra in Americana and “pops” items, as well as his fearless advocacy of thorny modernist scores. He was notably accomplished in terms of sheer conducting acumen. Players recall Lane as something of a martinet, not in the sense of his being musically inflexible, but rather for the near-inhuman exactitude he demanded from his musicians. “I learned a lot about precision from him,” said cellist Charles Bernard (in conversation with journalist Zachary Lewis), who played under Lane as both a student and as a member of the Orchestra. “He was picky almost to a fault. But he was also effective, and people really respected him. He prepared you for what could be out there in the real world.”

Lane’s strong musicianship made for exceptionally persuasive, easy-sounding performances of modern and contemporary music. “Cleveland’s audience is unusually sophisticated, believe it or not,” he declared in a speech to the Sir Thomas Beecham Society. “West of New York, I think it’s by far the most sophisticated audience you can find. You go to the west coast and it’s quite a different story.” In 1974, he conducted a double-bill of Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex and Perséphone (the latter, a Cleveland premiere). “I was able to do this, well because I was allowed to do it. You can’t do that in very many places. I’ve never been with an orchestra since then that had a public that would stand to listen to Persephone [sic] and Oedipus Rex the same night. It seemed to be quite successful here.” His program roster over the course of his association with Cleveland, though not exactly provocative by present-day standards, remains striking for its expansiveness, giving the impression of an aesthetic omnivore who cannot be pigeonholed into a particular stylistic stance.

In this context, his legacy in light music (fodder for the summer pops concerts) seems that much more impressive, lending him a chameleon-like virtuosity. (One thinks of other, more famous conductors, like Previn or Bernstein, whose careers also encompassed modernist and more popular musics.)

Nor were Lane’s efforts restricted to instrumental music. He was a major force (along with Michael Charry) behind a renascence of opera in Cleveland in his capacity as music director of the Lake Erie Opera Theater (LEOT), from 1964–70, following a protracted lull in Cleveland’s operatic activity after the Rodziński era (in the 1930s and early ’40s). Szell was far from indifferent toward opera himself, and conducted it at various points in his career. But the operatic repertory did not figure prominently in his work with The Cleveland Orchestra; not in the way that it had for Rodziński before him, who made significant triumphs in mounting operas at Severance, on a scale that is impossible today, given the permanent retrofitting of the stage for orchestral concerts (making a conventional operatic staging, with full scenery, physically impossible). Just as Lane’s symphonic programs would lead us to expect, his operatic roster shows him negotiating accessible, evergreen repertory works, while also programming some of the more approachable modernist masterpieces (by Prokofiev, Britten, and Poulenc). LEOT represented a significant artistic collaboration by a dozen different organizations, and had strong ties to Severance, where some of the operas were performed. In fact, the LEOT orchestra exclusively comprised members of The Cleveland Orchestra. It remains an important episode in the city’s artistic legacy — with Lane occupying a role at its epicenter.

Lane will continue to hold a special place in Cleveland’s cultural memory for his impressive list of Cleveland premieres, including (perhaps surprisingly) certain canonic works that are now so standard that it is difficult to imagine that they were rarities not so long ago. (These include a striking number of Cleveland premieres of various Mahler symphonies, which contributed to Lane’s being awarded the Bruckner Society of America’s prestigious Mahler Medal in 1971.) At Blossom, Lane gave the first performance in the area of Mahler’s Eighth Symphony, which was enthusiastically received. “It was a thrilling thing to do and I have enjoyed that probably as much as anything,” he recalled. His performances of Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie in 1973 (including at Carnegie Hall) were a particular triumph, prompting the composer himself to provide a grateful inscription on Lane’s conducting score:

Great indeed. Very great conductor. So precise, so dynamic. So profoundly a musician, a possessor of a technique so assuring who conducted this work with such perfection and impassioned commitment. With all affection, and admiration, Mr. Messiaen.

It’s hardly an accident that Lane made a cottage industry, later in his career, of taking posts with orchestras that, not unlike the Clevelanders post-Szell, required a skillful stopgap while searching for a principal music director. In this role, he was far more than a mere placeholder, gaining a reputation as the sort of musicianly staff sergeant keen to undertake the unglamorous scutwork of sculpting a large, unwieldy ensemble into an audibly better version of itself (one that then stood a better chance of attracting a marquee-name as principal director). Particularly noteworthy, in this respect, was his work with the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, where he was brought on from 1973–78, first as principal guest conductor and then artistic advisor, before Eduardo Mata’s appointment as music director. (This was after Lorin Maazel’s appointment as music director in Cleveland.) Dallas was, in a sense, the closest Lane came to achieving independence from Cleveland with an important ensemble of his own — alas, what should have been a career-catapulting opportunity was scuttled by funding problems. More successful, though less autonomous, was an auspicious professional collaboration with his former Cleveland colleague Robert Shaw in Atlanta during the late-1970s and 80s.

The professional relationships that Lane cultivated over his quarter-century at Severance are among the most compelling aspects of his legacy. Those who knew him seem, on the whole, to have thought well of him—admired him, even. For some, that admiration could shade into affection, which may been especially true of the Orchestra’s other conducting assistants, who would naturally have regarded him, in many cases, as something of a musical elder brother. A former assistant conductor (also under Szell) and longtime friend to the Orchestra, Michael Charry, maintained contact with Lane for more than half-a-century. Like Lane, Charry has remained active as a conductor and pedagogue; they are both exemplars of a distinguished confraternity of former Cleveland conducting assistants who continued to influence orchestral performance nationally (and internationally), long after their Severance days were over.

Of his Cleveland conducting colleagues, the most important to Lane’s career was surely Robert Shaw, who arrived at Severance close to a decade after Lane (despite being somewhat older) and developed a special professional camaraderie with him over the course of several decades. It is probably fair to say that, after Szell, it was Shaw who was Lane’s most powerful champion, elevating him to a significant post as a sort of guest-conductor-in-residence at the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra (from 1977–88), which Shaw (with Lane’s help) was steering toward the front rank of American orchestras. Lane recalled the strength — and the strife — of his rapport with Shaw, when he observed that “the relationship with Mr. Shaw was a very intense one as every relationship with Mr. Shaw is. It’s either intensely friendly or intensely unfriendly. And we have had both of these times.” He credited Shaw as the impetus for an major professional advancement within the hierarchy at Severance, to the level of Associate Conductor (in 1960), during their time serving together on staff under Szell:

I must say that was at Mr. Shaw’s suggestion … I don’t think Szell would have ever done it if Robert hadn’t gone to him and said, “This is a serious problem, because I have too many concerts which I don’t have the expertise to prepare quickly enough. Mr. Lane has too few concerts in my opinion. He prepares things quickly. I’m slow and I think he needs more concerts and I need fewer concerts.” And this argument which Robert presented two or three times eventually caused Szell to make this change.

Shaw didn’t exaggerate Lane’s alacrity in absorbing and rehearsing new repertoire. With his extreme eclecticism, Lane was arguably a more flexible musician than Szell, whose musical tastes had their limits. The elder maestro’s more exalted professional stature was such that he could afford to decline the performance of works that he found less than wholly sympathetic, including many of those contemporary works that, per Donald Rosenberg, Szell sometimes crushingly dismissed as “temporary music.”)

Certainly, we mustn’t assume that Lane personally championed every work that he conducted; unlike the major international music directors, he was never permitted by circumstance to graduate beyond a yeoman-like mandate to present most any work that might conceivably attract a respectable audience. It is difficult to discern just how high was Lane’s personal tolerance for the popular selections that he would often program with for pops concerts. He doesn’t seem to have actively disliked the popular repertoire that forms an exaggerated share of his recorded legacy; but it is also fairly clear from his comments that this repertoire, while lucrative, was not one that he held in overly high regard. (At least, Lane does not seem to have shared Bernstein’s zeal for popular American music; then again, a live performance of a medley from Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess with the Orchestra, while on tour in Vienna, shows Lane drawing delectable, idiomatic portamentos from the Cleveland strings.)

Other of Lane’s recordings with various Cleveland ensembles, some of them newly digitized, can be heard here. One might take as a starting point Lane’s Cleveland Pops recording of Arthur Benjamin’s Jamaican Rumba, which finds the orchestra dancing with nimble insinuation under Lane’s baton—Epic’s late-’50s stereo engineering wonderfully captures the ensemble’s glow.

It would do a disservice to Lane to imply that he was, at every turn, afflicted by a professional ill-luck of the always-a-groomsman-never-a-groom sort. (And he would have been the first to emphasize that he continued in secondary staff positions largely by choice, preferring to play a supporting role with a more distinguished orchestra, rather than to devote all his time and attentions to the comparatively limited artistic possibilities of a more provincial ensemble — though he did not disdain working with these more modest groups.) He enjoyed the musical directorship of two local orchestras, the Canton and Akron symphonies (from 1948–60 and 1959–83, respectively), bringing his expertise to bear upon them, and further cementing his contribution to Ohio’s musical life. Jones notes that “he didn’t have a big personality.” As a person, beyond his identity as a musician, she thinks he is best described as “honest.” And honesty, she speculates, was not necessarily conducive to the development of a more grandstanding career as major conductor. Yet Lane was a far from colorless personality. “He had a good sense of humor,” she says, likening the movement of his eyebrows when in a more jocular mood to those of Groucho Marx.

The latter half of his career led to mutually beneficial associations with several important orchestras (especially those of Dallas and Atlanta), yet Lane never relinquished his fealty to the Clevelanders. “The sense of rhythmic accuracy and the intensity behind the small notes, together with the sense of articulation, is what makes … the style of The Cleveland Orchestra, essentially,” he remarked. “You can talk about sound qualities and all of that, but these are the elements that make the style of this orchestra.” Of his career-long lookout for ensembles of comparable quality, he admitted to Rosenberg, “You never get it, but you try to approach it ... I’ve conducted many very good orchestras, but only the Chicago Symphony has made me feel I was conducting an orchestra on the level of Cleveland.” Lane’s summation of his mentor’s influence is suggestive of where his own artistic and vocational priorities lay, also:

The most important thing I learned from George Szell has only a casual relationship to music. It is basically ethical. … Making music is the most important thing you can be doing at the time that you are doing it. It is the thing you do best to create a little order in this world. And if you don’t believe that then you have no business being in music.

No appreciation of Lane would be complete without an acknowledgement of his dedication to music education, ranging from educational concerts for school children (an important tradition for the Orchestra) to professional preparation. Lane was at the heart of a bold initiative, the Blossom Festival School (now the Kent Blossom Music Festival) — a collaboration between the Orchestra and Kent State University — which brought coaching and performance opportunities at a high artistic standard to conservatory-level student musicians (he was co-director of the school from 1969–73). Even in semi-retirement, Lane continued to serve as a conductor-pedagogue with the Cleveland Institute of Music’s orchestra, influencing myriad students whose careers have taken them far afield (“Louis loved teaching,” Jones says). An honorary citation accompanying the conferral of Columbia University’s prestigious Alice H. Ditson Award (1972) may provide as eloquent a summation as any for Lane’s character and musical contribution:

It is your deep commitment to the American composer that we celebrate. You have conducted American music of widely divergent musical styles. … You have introduced young audiences to new music. You have not sought the easy glamour that often accompanies premiere performances; rather you have offered the second and subsequent performances that are even more important to composers and their audiences.

— Dane–Michael Harrison was the 2023–34 season archives research fellow. The fellowship is an opportunity for graduate music students from Case Western Reserve University to work with The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

Photographs and non-commercial recordings come from the collection of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

A debt of gratitude is due to former principal pianist, Joela Jones, and former staff conductor Michael Charry, who graciously shared their memories of the Lane era in online interviews

Want to learn more?

For historical and biographical information, including authors’ observations and interpretations, the following sources were among those consulted:

- Charry, Michael. George Szell: A Life of Music. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2011.

- Charry, Michael. “Louis Lane and the Cleveland Pops Recordings” (liner notes essay). In Louis Lane Conducts The Cleveland Orchestra. The Complete Epic and Columbia Collection. Sony Classical 19658833742, 2004, compact discs.

- Rosenberg, Donald. The Cleveland Orchestra Story: “Second to None.” Cleveland: Gray and Company, 2000.